How seroprevalence is helping us in the fight against COVID-19

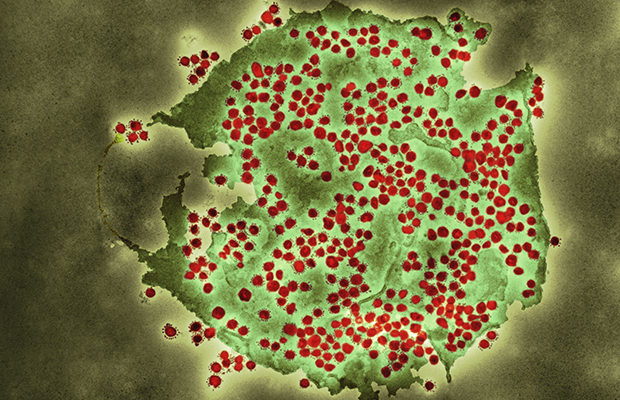

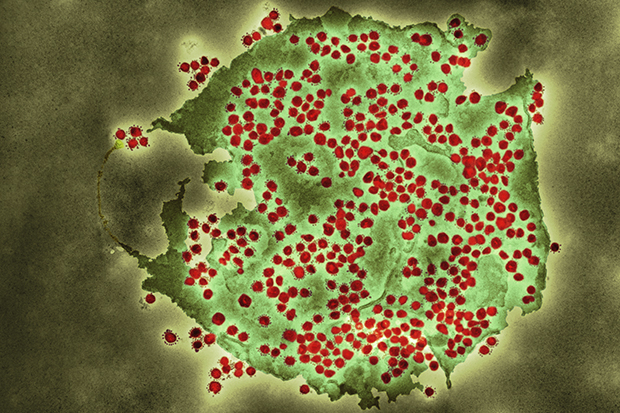

Coloured transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of a SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus particle isolated from a UK case of the disease Covid-19.

PHE’s Head of immunisation Dr Mary Ramsay describes how testing blood samples is helping us gather crucial data on the spread of COVID-19.

Controlling the spread of coronavirus (COVID-19) requires the ability to find people with mild infections and those with no symptoms who would otherwise remain undetected.

This is important to help work out the true number of infections in the population and to establish the extent to which the infection has spread across the country.

Using this information, we can estimate the proportion of the population that has been infected with COVID-19 up to a point two weeks before the sample – the scientific term for this is seroprevalence.

This information helps us to better understand how COVID-19 has spread in different age groups, in different parts of the country and in different settings – this helps us to decide how best to slow the spread of the virus.

PHE is working with NHS Blood and Transplant service and NHS laboratories across the country to gather this data through the testing of a small amount of blood from donor samples and other left over samples in participating laboratories across England. In addition, we’re also using samples from specific groups of people to learn about how the virus has spread in certain settings.

National surveillance

Since late February, we have been providing seroprevalence data to government and to SAGE, and for the past several weeks have been publishing antibody prevalence estimates across England, based on blood samples taken from healthy adult blood donors by NHS Blood and Transplant.

Our surveillance in blood donors provides an overall estimate of the number of adults in England that have developed antibodies against COVID-19 and identifies the areas where prevalence is increasing.

These data suggest that the initial spread of the infection happened more quickly among younger adults in areas like London, with infections among older people and in other areas occurring slightly later.

While it is too early to draw hard and fast conclusions about how coronavirus spreads, the patterns we’ve seen so far most likely reflect differences in how different groups interacted with each other, such as through work and how they travel to work. It also highlights the need for further research to establish how age may affect antibody response to the virus.

As lockdown restrictions continue to lift further and we return to a more normal way of life, this surveillance will play an important role in monitoring any new spread of the disease, building on other national data being gathered by the ONS and Ipsos MORI.

Focusing on specific groups

We are collecting blood samples to find out more about how the virus is behaving among specific groups and settings, such as among healthcare workers and in schools.

We are currently leading a voluntary study – Schoolkid surveillance, or sKIDs – to monitor the prevalence of COVID-19 among pre-school, primary and secondary school pupils and teachers. This will collect data from thousands of students and staff from over 100 schools across England, with the first results expected in the summer.

Studies like this will be vital in ensuring the safety of students and staff returning to school in the coming weeks and months. The data will help us to better understand the levels of asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 infections in younger healthy people that may have otherwise remained undetected, as well as to understand the extent of the spread of the virus in school settings. We will use the results to inform how we can monitor COVID-19 in educational settings in the autumn term.

The sKIDs study is just one of several ongoing surveillance programmes to monitor COVID-19 in children and young people from birth.

As well as shedding light on how the virus has spread, our surveillance is also helping us to understand the extent to which antibodies to COVID-19 could protect people against future infection.

While we know that people produce antibodies in response to being infected with COVID-19, we don’t yet know whether this means they are protected from catching novel coronavirus again and how long that protection may last – a crucial piece of the puzzle.

Our SIREN study is helping to answer these questions by testing 10,000 healthcare workers over the course of a year, with blood samples, nose and throat swabs taken regularly to determine new infections and measure antibody response. Data will be collected, recording history of infection and any new symptoms that appear, with initial results expected later in the summer.

You can read the latest findings from our seroprevalence work in PHE’s weekly surveillance report.

View original article

Contributor: Mary Ramsay