Tackling London’s ongoing COVID-19 health inequalities

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a devastating year which has touched every corner of our lives and the consequences have been felt deeply in Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities who have been disproportionately affected by the virus.

Recent analysis by my team at PHE London has revealed that sadly ethnicity continues to be a major factor in the health outcomes of communities during the second wave of the pandemic. Deprivation is also a key factor.

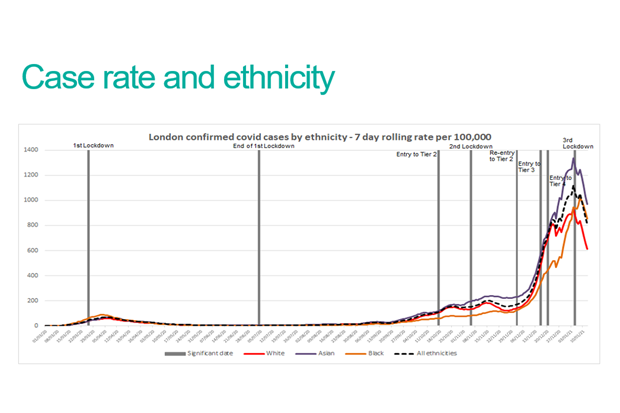

Case rate and mortality data shows London’s Asian populations have been worst affected during the second wave to date, followed by Black communities. In a similar pattern to the first wave, both Asian and Black communities continue to experience significantly higher case rates and deaths than their White peers, bringing sadness and loss to many Londoners and their communities.

The data also shows the highest numbers of COVID-19 cases have been consistently observed in more deprived areas during the second wave.

These findings emphasise the importance of the work being undertaken by the wider public health system to tackle the issues faced by Londoners from the worst affected communities and areas. Individuals can also help by taking up the vaccine when eligible, getting tested and seeking treatment early if they develop COVID-19 and their symptoms worsen.

What did our research find?

- At around the peak of first wave of the pandemic, compared to White Londoners, Black Londoners had around two and a half to three times the risk of dying with COVID-19 (within 28 days of diagnosis) and people of Asian ethnicity had up to twice the risk.

- In the second wave, we are seeing a higher risk in Asian Londoners at 1.7 times the risk of dying from COVID-19 (within 28 days of diagnosis) compared to the White population. For Black Londoners, the risk is 1.5 times higher, but less than in the first wave.

- Asian Londoners have been impacted hardest in the second wave, in part due to the geographical pattern of spread of the virus at the start of the second wave which predominantly took place in boroughs in the north east of the capital, where many of our city’s Asian communities live.

- Since the start of the year, we have seen a higher proportion of cases identified in our Black communities, increasing from around 10% of cases in early December to nearly 15% in mid-January. A relatively high proportion of cases have been seen in Asian Londoners in January who have accounted for around a quarter of cases, though they make up just under 20% of London’s population.

London-wide initiatives to address inequalities

Our previous ‘Beyond the Data’ report published in 2020, looked at impacts on BAME communities during the first wave and the stakeholders we spoke to pointed to a range of longstanding inequalities and socioeconomic factors which may be leading to poorer outcomes from COVID-19 among these populations. The ONS has also since concluded that a large proportion of the difference in the risk of COVID-19 mortality between ethnic groups can be explained by demographic, geographical and socioeconomic factors, such as where you live or the occupation you’re in.

These are deeply rooted issues and change will not happen overnight so, as we continue the long road to addressing health inequalities, it is important that people from London’s worst affected communities are well supported by us in public health and our partners in the wider system. Much has been achieved in London in terms of scaling up community testing, key worker testing, local contact tracing, helping staff in the transport network to be as safe as possible, as well as the incredible efforts from the Boroughs to help vulnerable people and those who need to self-isolate. I am regularly speaking to faith leaders and community forums across London about vaccine hesitancy and how we can engage people in a culturally competent way. National government is also keenly focused on the issue.

Other activities include:

- Community Champions scheme – Over £23 million is being allocated to 60 councils and voluntary groups across England, including seven of London’s worst-hit boroughs, to expand work to support those most at risk from COVID-19 and boost vaccine take up.

- Multi-lingual information and communications – Advice, information and alerts relating to COVID-19 have been produced in a wide variety of channels and languages under the Keep London Safe campaign to ensure that all Londoners can access important information relating to the pandemic.

- London’s Public Health Faith and Community Forum – which routinely has over 200 representatives taking part in its monthly meetings.

- London’s Health Equity Group – its membership is drawn from London’s faith and community groups, the business sector, as well as national experts to monitor progress addressing health inequalities and support action on the ground.

What can individuals do to protect themselves from COVID-19?

While our findings emphasise the importance of wider ongoing work to tackle inequalities during this pandemic, individuals also of have a vital role to play in protecting themselves. There are a range of things that people can do to reduce their chances of both catching the virus and falling seriously unwell.

These include:

- Taking up the vaccine when it is offered and encouraging relatives and friends to do the same. Recently-published analysis found Black people over the age of 80 were half as likely as their white peers to have been vaccinated against COVID-19 by 13 January.

- Taking up asymptomatic community testing when it is offered. People from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds are more likely to work in frontline jobs or occupations which prevent them working from home. If this applies to you, taking up asymptomatic testing will give you a better chance of identifying the virus early and stopping you from unknowingly spreading it to friends or family. If you are required to self-isolate, you may be entitled to financial support.

- Getting tested and self-isolating immediately if you have symptoms. You must self-isolate and get tested as soon as you develop any COVID-19 symptoms, which include a high temperature, a loss or change in your sense of smell or taste or a new, persistent cough. The quicker you isolate the less chance you have of passing on the virus to loved ones.

- Seeking treatment early if you feel unwell. PHE’s report on pre-existing health conditions and ethnicity showed that the timing of getting tested and seeking treatment may be contributors to poorer outcomes in some ethnic minorities. COVID-19 can cause oxygen levels in the blood to drop to dangerously low levels without the patient noticing. A pulse oximeter is an easy and affordable way of regularly monitoring your blood oxygen levels, enabling you to seek treatment early if they do start to fall.

The pandemic has been challenging on so many levels for communities who are dealing with not only the immediate impacts of COVID-19, but also wider consequences such as worsening physical and mental health, social disruption and economic anxiety.

I know that because BAME communities have been and continue to be disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, that this has caused a sense of despair, sadness and anger, which I have heard first hand. For some, this may also cause them to disengage from the epidemic and become hesitant to having the vaccine and we must listen to and address these concerns.

However, the power rests within our hands to work together to tackle these inequalities – whether in protecting ourselves, reducing transmission by following the rules, or taking up the vaccine when it is offered to us. These actions will help ensure that this unequal toll on our communities is challenged, allowing all of us to take back some control of our lives, protecting our health and that of our loved ones, and starting the journey to life beyond this disease.

View original article

Contributor: Kevin Fenton