What do we know about the new COVID-19 variants?

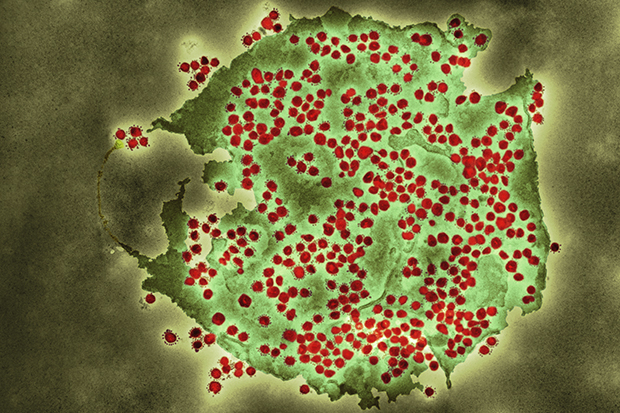

Coloured transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of a SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus particle isolated from a UK case of the disease Covid-19.

All viruses mutate over time. For this reason, very early on in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a genome sequencing capability was established in the UK to monitor changes in the genome of the virus over time.

This sequencing capability allowed us to detect the emergence of the variant first seen in South East England, which has since swept the country. Since then alerts have been raised about variants first seen in South Africa, Brazil and Japan but which have been found in several other countries including the UK. Many more are likely to be identified in the coming months.

Why are we now seeing these variants?

All viruses naturally mutate over time, and SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 disease, is no exception. Over time, changes can build up in the genetic code of the virus, and these new viral variants can be passed from person to person. Most of the time the changes are so small that they have little impact on the virus. But every so often a virus mutates in a way that benefits it, for example allowing it to spread more quickly, and causes us to be concerned about changes in the way the virus might behave. In this case the variant may be considered a ‘variant of concern’ by the UK government.

Most mutations are not a cause for concern. Scientists around the world have been monitoring these throughout the pandemic. In the UK, we have a comprehensive genomics system which allows us to detect these different mutations. We have contributed around half of the sequences in the global SARS-COV-2 genome repository (GISAID).

We have now announced a programme to help support international capacity to identify variants of concern. The New Variant Assessment Platform is led by PHE working with NHS Test and Trace and academic partners as well as the World Health Organization’s SARS-CoV-2 Global Laboratory Working Group.

What do we know about the variant first identified in the UK?

The variant, known in the UK as VOC202012/01, includes multiple mutations in the spike protein, including N501Y. The spike protein is the part of the virus which first attaches to a human cell. These changes have resulted in the virus becoming about 50% more infectious and spreading more easily between people.

We know as evidence shows that the infection rates in geographical areas where this particular variant has been circulating have increased faster than expected despite control measures being in place, and the modelling of cases over time has demonstrated that this variant has a higher transmission rate than other variants in current circulation.

We do not know for certain the mechanism for this increase in transmission but it has been suggested that this variant is more effective at binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, or ACE2 receptor, the protein that provides the entry point into the body for the coronavirus.

How long has this variant been in circulation?

Genetic evidence suggests this variant emerged in September 2020 and then circulated at very low levels in the population until mid-November.

The increase in cases linked to the new variant first came to light in December when PHE was investigating why infection rates in Kent were not falling despite national restrictions. We then discovered a cluster linked to this variant spreading rapidly into London and Essex.

What do we know about the variant first identified in South Africa?

The variant first identified in South Africa is called VOC202012/02 and appears to have emerged around the same time as the variant originating in the UK. It has also been seen in a number of other countries. It shares the N501Y mutation to the spike protein but also has a number of other mutations including E484K.

Laboratory tests have shown that the E484K mutation may be able to escape the body’s antibodies to some extent and is therefore of potential public health concern, so it’s one we’re monitoring closely. All cases with this mutation are currently being followed-up closely and monitored in the UK.

The UK Government imposed a ban on direct flights from South Africa and restrictions on flights to the country in order to reduce the number of people infected with the variant entering the UK. There are now 33 countries on the UK’s travel ‘red list,’ which is being enforced in an effort to stop the spread of variants.

Additional surge testing and sequencing is being deployed in a number of locations where the COVID-19 variant first identified in South Africa has been found. Testing will, in combination with following the lockdown rules and remembering ‘Hands. Face. Space’ help to monitor and suppress the spread of the virus, while enabling a better understanding of the new variant.

What about the variants emerging from Brazil?

Two variants of interest have also been identified in Brazil. The first variant is currently classified by PHE as a ‘variant under investigation’ (VUI) 202101/01 – this variant has a small number of mutations but does include E484K. This variant has been detected in 11 countries so far including the UK. The spread and significance of this variant remains under investigation and PHE will publish regular updates on the number of cases detected.

What about the second variant originating from Brazil?

The second variant was detected in Manaus, a city in North West Brazil, and travellers from Brazil arriving in Japan and is also considered to be a ‘variant of concern’ VOC202101/02 that has similar spike protein mutations to the South African variant. No cases have been confirmed in the UK to date.

Are these variants more dangerous?

UK investigators have calculated that there is a realistic possibility that being infected with the variant that was first identified in the UK is associated with an increased risk of death compared to earlier version of COVID-19 that was circulating. Early evidence suggests the new variant could be about 30% more deadly but more data are being collected and the position will become clearer over the coming weeks. The absolute risk of death is still low.

As more cases of the South African variant are confirmed, we’re also monitoring this variant closely for any changes in severity, along with international partners.

The best way to protect against them is to continue following the stay at home guidance and to practice hands, face, space whenever you leave the home.

If you have had the original strain can you catch a new one as well?

Our investigations are underway to find out more about these new variants. This includes whether immunity from a previous infection protects you against infection with a variant. We monitor reinfections (people who have two COVID-19 infections) in the community nationally, and through our large healthcare worker study SIREN, in partnership with the NHS.

How were these variants identified?

COG-UK, including the UK four public health agencies, sequences a proportion of all positive cases in the UK to help us determine how the virus is behaving – this allows us to pick up variant in the community. In addition we undertake targeted testing and viral sequencing of certain groups of people, such as those entering from Southern Africa at present.

How many cases of the different variants are there?

PHE publishes the latest confirmed numbers for new COVID-19 variants including a breakdown of numbers for the UK and for the 4 devolved administrations.

Do the current vaccines work against the variants?

It is very unusual for any variant virus to render a vaccine completely ineffective, however variants can alter the performance of vaccines to some degree. Studies are ongoing to assess this in for multiple variants, but both laboratory and clinical studies are needed to be sure. The variants detected in South Africa and in Manaus, Brazil are the more concerning for potential effect on vaccines.

We are continuing efforts to understand the effect of the variants on vaccine efficacy. If required, future vaccines could be redesigned and tweaked to be a better match to these variants, as is the case for seasonal flu vaccines.

It’s important that we keep looking at data and understanding the performance of vaccines in the real world, as well as in laboratories, but the trial data is very persuasive; these are highly effective vaccines and we would expect that to translate into what happens in real practice.

As we continue to monitor new variants remember that the best way to protect against the virus is to continue following the stay at home guidance and to practice hands, face, space whenever you leave the home.

View original article

Contributor: Blog Editor