How science can protect us from the health effects of climate change

The impacts of climate change are already being seen around the world.

The Earth is warming, rainfall patterns are changing, and sea levels are rising, increasing the risk of heatwaves, floods, droughts, wildfires and other natural hazards.

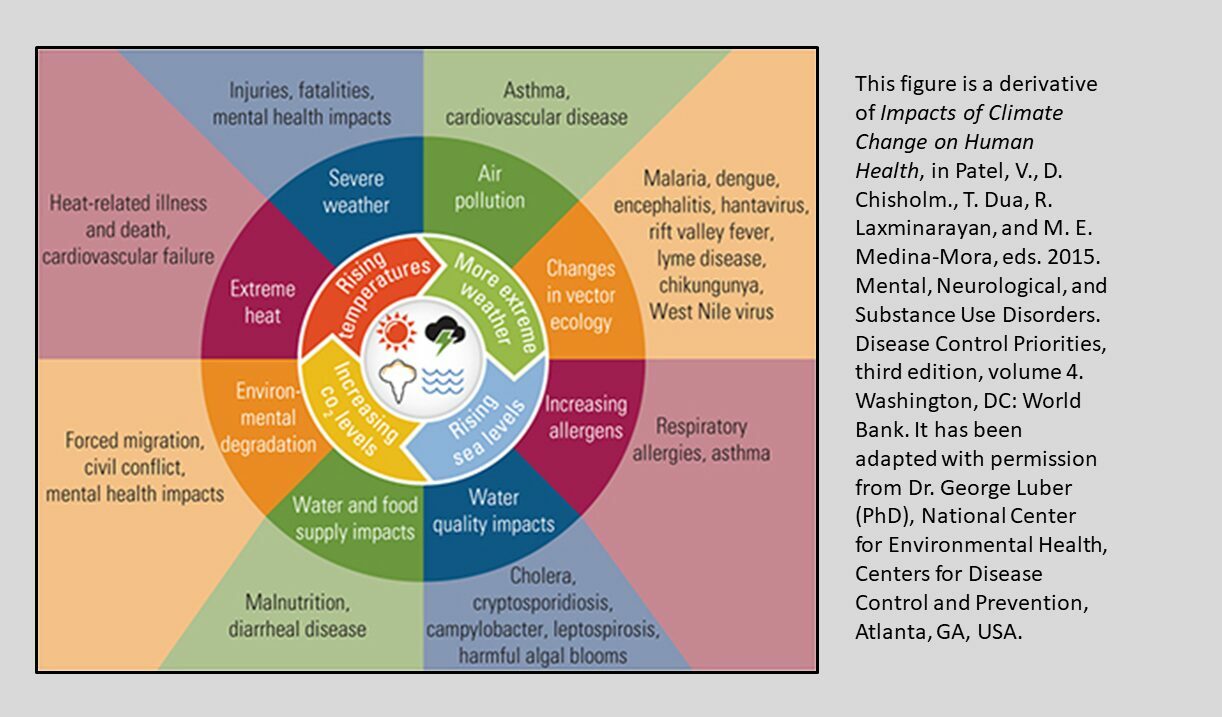

These changes pose one of the greatest health security threats we face, potentially impacting the air we breathe, the quality and availability of our food and water, the risk of infectious diseases and wider impacts on our mental health and wellbeing.

Though climate change is often referred to as a global problem, no country or community is immune to its effects.

Here in the UK, high summer temperatures already have significant health consequences. In Summer 2020 we saw 2,556 all-cause excess deaths (excluding deaths from COVID-19) during episodes of heat and it’s projected that numbers of heat related deaths will potentially triple by 2050 if no action to mitigate this is in place.

Warmer temperatures are also one of the factors that could see invasive mosquitoes establish in parts of the UK, and diseases they carry being passed to humans.

Climate change is also likely to impact on our air quality. Changes in weather patterns could increase episodes of ground-level ozone or other particulate matter potentially leading to increased hospital admissions due to asthma, or other respiratory or cardiovascular diseases.

And disrupted food production around the world, particularly in the Global South, could also pose food safety and security risks including in the UK.

Whilst many of these impacts will be experienced by everyone, they will disproportionately affect the most disadvantaged, further increasing health inequities.

It is clear that further and faster action is needed to understand and mitigate the risks that climate change poses to our health and health systems, and science has a major role to play in this global effort.

Translating climate science into action

Our scientists study the health effects of climate change, provide early warning and response to extreme weather events, quantify the health impacts of air pollution and monitor the risks posed by changes in the distribution of vector-borne disease or disruptions within the food system.

Working in multi-disciplinary teams also means we can draw on expertise in areas like global health, emergency preparedness, resilience and response, data and analytics, behavioural science and health inequalities.

Much of our work is carried out in partnership with others, from local authorities through to national government and academia, including the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Environmental Change and Health, a partnership between UKHSA and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, University College London and the Met Office.

We are engaged in a range of international work, for instance through our contribution to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change which provides evidence for policy makers all over the world.

We also recently led a global science partnership for the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction Hazard Definition and Classification Review and its Hazard Information Profiles Supplement.

These major scientific contributions have built shared understanding of hazards to inform experts working in disaster risk reduction, emergency management, climate change and sustainable development.

UKHSA is also one of the founding members of Health and Climate Working Groups within the International Association of National Public Health Institutions (IANPHI) and the Cochrane Group. We recently co-led the conceptual development of two landmark position papers in collaboration with IANPHI (Roadmap for Action on Health and Climate Change) and the WHO Regional office for Europe (Zero regrets: scaling up action on climate change mitigation and adaptation for health in the WHO European Region).

Looking forward, we are working on the fourth iteration of the Health Effects of Climate Change in the UK, a landmark report produced periodically and last published in 2012 which feeds into UK’s National Adaptation Programme.

The report will bring together the latest UK climate change projections and assess the health risks posed by climate change, like weather and its extremes (temperature, flooding, droughts and wildfires), air pollution, allergens, UV radiation, infectious diseases, especially vector borne disease (transmitted by ticks and mosquitoes), water and foodborne illness.

New aspects of the report include an assessment of the role that adaptation action (such as changes to our living environments or behaviour) can take in reducing future climate-related health impacts.

And as part of the National Adaptation Programme, UKHSA leads on the development and delivery of a Single Adverse Weather and Health Plan to replace the Heatwave and Cold Weather Plans for England. This will provide updated guidance on cold and hot weather, drought and flooding informed by scientific evidence nationally and internationally.

Achieving a step change in the public health response to our changing climate

To reduce the impact of climate and environmental change on health we need a step-change in the public health response.

This will include strengthening the scientific evidence to guide our actions, including interventions and adaptations that mitigate climate health risks, as well as building our understanding of whether these interventions are working.

We will need to work with funders to ensure evidence gaps are addressed and find new ways to make evidence accessible to decision makers.

Developing risk assessment tools as well as impact and outcome metrics at the national and local level is a key part of this.

And in all of our work we will need to forge stronger and deeper partnerships with local government, national government and academia.

Over the coming months, we are bringing together our work on climate and health as part of a new Centre for Climate and Health Security based within UKHSA, which will help us make the step change that we need to respond to the inevitable health impacts of the climate emergency.

View original article

Contributor: Isabel Oliver